Mary Ellen Pleasant was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1814 into a free, middle class black household. There were no schools in the city for black children, so when Mary Ellen was seven years old, her father took her to live with business associates on Nantucket Island which had a “colored” school.

Mary Ellen Pleasant

Unfortunately, the Hussey family of Nantucket were less than honest. They pocketed the tuition money from her father but didn’t send Mary Ellen to school. Instead, Mary Ellen was put to work in the Hussey general store. Recognizing the balance of power based on skin color, Mary Ellen worked hard to be indispensable to the Hussey family.

She was charming and friendly, brilliant at selling to every customer who came into the store. She helped the Hussey family make money while learning all aspects of their business. She used her experience and knowledge to amass a fortune later in life. She even remained on good terms with the Hussey family throughout her life.

She had arrived in Nantucket just as the whaling industry was creating vast fortunes, giving her a front row seat to the earliest boom town in the U.S. Boom towns shake up the roles of race and gender, at least temporarily. White, Indian, and black people worked together in the whaling business. As the men moved into higher paying jobs on the docks and on whaling ships, women took over running the shops, hotels, and other businesses that supported the whalers.

One of the centers of growing wealth was Newtown, a free black community separated from Nantucket by a fence. Newtown’s business leaders used some of their wealth to support the abolitionist cause. In 1841, Frederick Douglass was invited to speak at a local abolitionist meeting. He talked about his life as a slave and his escape from slavery. His speech inspired Mary Ellen to fight for an end to slavery.

In 1842, she moved to Boston, where she met her first husband, James W. Smith, a businessman from Charles Town, West Virginia. Smith was an abolitionist who bought slaves at slave auctions so that he could free them. Unfortunately, Smith died two years after they married. When his estate was settled, Mary Ellen inherited $45,000 ($1.2 million today).

In 1848, she married JJ Pleasant, but he soon abandoned her to join the California gold rush. Mary Ellen followed JJ to San Francisco in 1852, only to discover he had joined the crew of a steamship that operated a regular route between California and Panama. Mary Ellen decided to secure her own future. Like Mark Twain, she quickly figured out that there was more money to be made in San Francisco than in the mining camps.

Mary Ellen made money as an investor and as an arbitrager. She used part of her inheritance to loan money at 10% interest. As an arbitrage trader, she bought gold and then exchanged it for silver. When she had amassed a sufficient amount, she sold the silver to eastern investors for an incrementally higher price than she had paid. By 1858, she was worth more than $150,000 ($4.2 million today).

She was successful because she was able to easily build rapport with people at every economic level of San Francisco. However, she preferred to stay in the shadows, operating through white men. San Francisco was a melting pot of whites, Hispanics, blacks and Chinese immigrants. But it also overflowed with racists who blamed black and brown skinned people for everything from “stealing” jobs from whites to being criminals. Chinese immigrants were regularly subjected to ICE-style raids by mobs that resulted in property destruction and murder. For non-whites, there was no legal recourse.

In 1854, the California Supreme Court ruled that non-whites were banned from testifying against whites in court, in the Folsom v. Leidesdorff case. The ruling allowed James Folsom, a politically connected white man, to steal an estate valued at $1.4 million ($38 million today), from the heirs of black entrepreneur, William Alexander Leidesdorff. A state law codified this grotesquely racist decision.

Recognizing the political reality, Mary Ellen protected herself by staying in the background and quietly using her wealth to try to change the status quo. She donated to efforts to overturn the California state law and supported a variety of abolitionist newspapers and organizations. Her most spectacular and risky donation was to finance John Brown’s revolution.

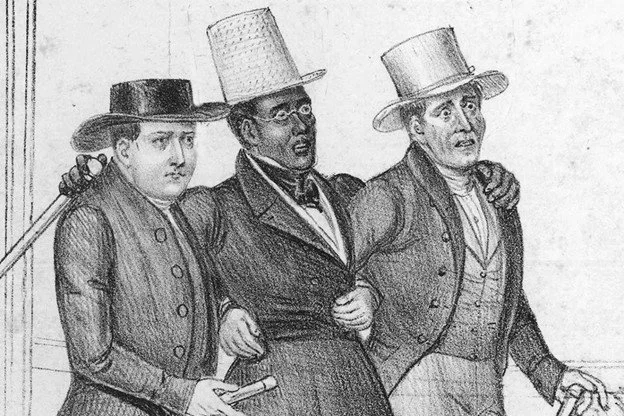

John Brown was a murderer who suffered from delusions of emulating the Haitian Revolution in which black slaves led by Toussaint L’Ouverture overthrew French colonialism. His revolution would begin with a slave insurrection in West Virginia. But first, he would need to steal guns and ammo from the U.S. military depot at Harper’s Ferry.

Mary Ellen gave Brown a bank draft for $45,000 ($1.3 million today) to underwrite his revolution. She later traveled to West Virginia, meeting with slaves to encourage them to join the revolution. Alas, she misread their enthusiasm. The slaves didn’t rise up in rebellion and Brown’s raid was crushed in about 48 hours. (John Brown was hanged a year later, becoming a thoroughly undeserving martyr to the abolitionist cause.)

Mary Ellen briefly went into hiding before returning to California in 1859. Most of her fortune had been blown on the revolution, but she insisted she never regretted her choice. She set about rebuilding her fortune.

After the Civil War, she decided to use the new federal Civil Rights Act of 1866 to challenge local laws which prohibited black people from riding the San Francisco streetcars. A white friend boarded the chosen streetcar and watched as the conductor zoomed by the next stop where Mary Ellen was waiting to board. Mary Ellen sued for discrimination.

A streetcar

In Mary E. Pleasants v. NBMRR, the court ruled that the local streetcars must be desegregated and awarded her $500 ($6,863 today) damages. She was able to testify because the old state law had been repealed. The case was widely cited in the 1950’s and ‘60’s civil rights litigation.

The inevitable backlash to her lawsuit was a smear campaign alleging that Mary Ellen was a former slave, a mammy, a voodoo priestess, or a madame, depending on which pseudo-journalist one chose to read. The backlash included the election of a white supremacist as governor in 1867 who rammed through laws stripping legal rights from non-whites.

However, voters quickly tired of the racists, who whined about the unfairness of life, while catering to the wealthy and ignoring the problems faced by most people. In 1871, a reformer was elected governor after promising to address the housing shortage and food insecurity faced by most Californians. One of his biggest campaign donors was Mary Ellen.

The new governor had lived at the downtown San Francisco boarding house owned by Mary Ellen. They remained friends until his death. Her closeness with the governor proved that Mary Ellen had the connections and the money to get things done. She used both to quietly underwrite a political and social revolution.

Mary Ellen Pleasant died in 1904, leaving an estate valued at $600,000 ($16.2 million today). Her final wish was that people would remember that she had devoted a large part of her fortune to the cause of ending slavery.

Mary Ellen Pleasant’s story appears in Black Fortunes, by Shomari Wills (2018). A movie about her life, “Meet Mary Pleasant”, is available on Netflix and Amazon Prime.