The line between a freedom fighter and a terrorist depends entirely on one’s point of view. Freedom fighters are heroes; terrorists are despised. Today, there are still arguments about which category best suits Michael Collins.

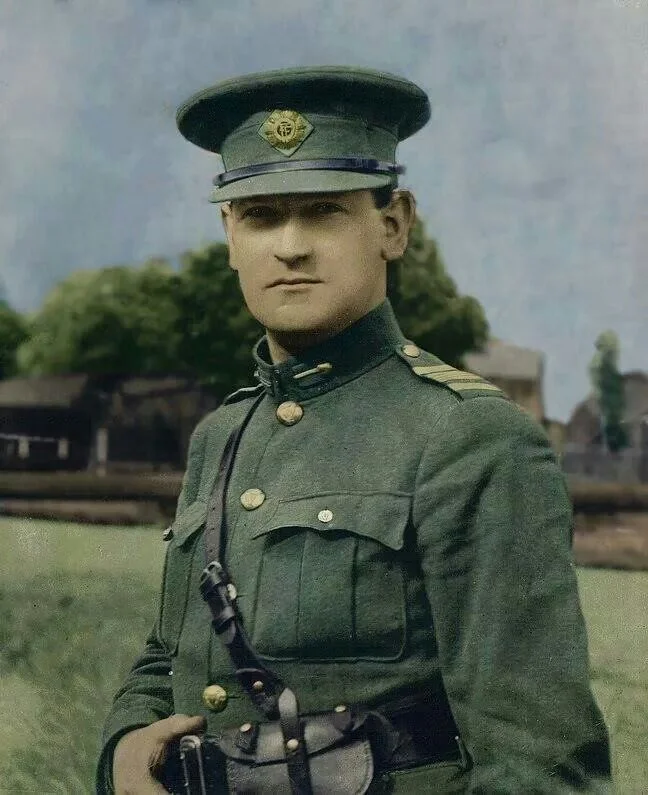

Michael Collins was born on October 16, 1890. He was nicknamed the Big Fella because he was almost six feet tall, broad shouldered and athletic. He charmed people he liked, but was impatient and rude to people who annoyed him. No one had a neutral reaction to this brash, charismatic man.

His life was shaped by stories of the landlord-tenant system that dispossessed Irish Catholics like his family and the 1845 – 1846 potato blight, when millions of Irish either starved to death or emigrated to the U.S., Canada, or Australia. Not surprisingly, he became a supporter of independence for Ireland.

In 1916, Collins joined the rebels who occupied the Central Post Office building in Dublin on Easter weekend. Their political leader, Eamon de Valera, declared independence for Ireland. A week later, the rebellion was ruthlessly suppressed and de Valera was smuggled off to America. Sixteen leaders of the Easter Uprising were hanged by the the British. Other rebels were sent to prison, including Collins.

After leaving prison, Collins created a two-pronged attack against British rule in Ireland. The first prong was an intelligence system composed of ordinary people like clerks, secretaries and janitors. The British might rule Ireland, but they relied on local Irish to staff the government. Collins could soon boast that he received copies of official communications before the intended British recipient received them.

The second prong was violence. His enforcers, known as the Apostles, assassinated informants and suspected traitors. He also commanded flying columns, small squads of fighters who roamed the countryside planting bombs and skirmishing with the police.

Collins meanwhile openly rode his bicycle around Dublin passing through British checkpoints. He was once recognized by a policeman who threatened to shoot him, but Collins pointed out that the checkpoint was surrounded by his supporters and the policeman would be shot dead if he reached for his sidearm. Then Collins stepped back on his bike and rode away.

It was a dirty war on both sides with murders, collective punishment and widespread suffering of civilians. Irish-Americans underwrote the rebellion with money and guns. They also pressured the U.S. government to put pressure on the British government.

By 1921, the pressure paid off and the British government agreed to negotiate with the Irish rebels. The rebel leaders like de Valera never educated the Irish public that any deal would involve compromises, much as the Brexiteers today never acknowledged the financial and political tradeoffs of Brexit.

The deal that emerged granted independence, but excluded the six counties of Ulster which were predominantly Protestant. Collins and the other negotiators were branded as traitors for giving up Ulster, even though they lacked the negotiating leverage to force the British to allow a unified Ireland. The new Irish state immediately descended into civil war.

After the civil war ended the Irish Republican Army (IRA) continued fighting for unification until the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998. This Agreement finally brought peace to Ireland along with an open border between Ulster and the Republic for the free movement of goods and people. The open border and Irish peace are now threatened by a no-deal or hard Brexit.

Collins didn’t live to any of this. He was killed by a sniper on August 22, 1922 while inspecting his troops, just shy of his 32nd birthday.

Collins lived like an action hero repeatedly defying death with enormous verve and humor. To read about more of his adventures, see Michael Collins, by Tim Pat Coogan (1992).

Want to receive this blog straight to your inbox? Sign up for my mailing list.