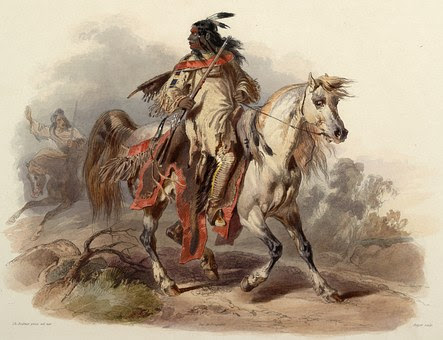

Early in the morning on December 29, 1890, cavalrymen from the U.S. Seventh Cavalry descended on a group of Lakota (Sioux) Indians camped in a ravine at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. The cavalrymen had been ordered to confiscate all the weapons in the encampment.

The Lakota were Ghost Dancers, practitioners of a new religion sweeping through Indian Country. They were camped in the ravine because it offered shelter from the winter weather. The day before, they had surrendered to the cavalry troops after fleeing violence at a nearby reservation.

The cavalrymen upended the Lakota shelters and scattered the contents in their search for weapons much like a modern SWAT team searching the premises of suspected violent felons. As two cavalrymen tried to take a gun from an Indian, the gun fired. No one was hit.

But four Hotchkiss guns set up on the rim of the ravine, which fired one shell per second, opened fire at point-blank range. Most of the Lakota men died fighting a hopeless delaying action while their women and children tried to escape. Some Indians who escaped the bloodbath in the ravine were chased across the prairie and gunned down.

The cavalry lost 30 dead, and 18 soldiers received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Estimates of the Lakota dead vary from 150 - 300, mostly women and children. Most Americans were more proud of the fighting spirit of the cavalrymen than appalled at the death of Indians.

Why did the cavalry use excessive force against a group of half-starved Indians? Horrific violence doesn’t happen in a vacuum, so it helps to look at what was happening in America.

In 1890, the national census confirmed what many Americans already feared about the country’s demography. A third of the population consisted of Southern and Eastern European immigrants most of whom were Catholic. Adding these darker-skinned Europeans to the Hispanics in Western states and blacks in the South meant America was becoming browner—and less of the white Protestant country it identified as.

By 1890, more Americans were living in cities and working on the factory floor than living in the countryside working on farms, which challenged America’s identity as a society based on agriculture.

Most Americans were also poorer due to the Panic of 1873, a financial meltdown caused by corrupt Wall Street financiers. Indebted farmers screamed for relief from banks. Factory workers struggled to protect their jobs and wages. The Robber Barons of the Gilded Age used some of their obscenely huge profits to hire company thugs to kill union organizers and fixers to ensure politicians didn’t look too closely at their businesses. The Middle Class found their financial and social standing squeezed on all sides.

America was falling apart. Reform-minded Americans decided to save America by integrating all the disparate pieces. An example that still exists is the Pledge of Allegiance, which was created in 1891 to integrate immigrant children. Unfortunately, reformist zeal to assimilate the disparate pieces smacked into another American tradition: racism.

And that brings us back to the Lakota Ghost Dancers at Wounded Knee. Reforming Americans had long since decided that Indians had to be assimilated because Indian culture was inferior to white culture. They were frustrated that it was taking so long. Then a new religion swept through Indian Country in 1889 – 1890.

The Ghost Dance emphasized peaceful relations with whites, working for wages, education, and a belief in a better world to come. Ghost Dancers mixed Christian practices with traditional beliefs. American reformers were appalled. The Indians weren’t assimilating; they were indulging in a religious cult and they needed to be stopped.

The military also had an agenda. By 1890, the Indian Wars were officially over and Congress was threatening to cut military appropriations. The Army needed to prove it was still needed, and a quick round-up of rebellious, non-assimilating Indians was the perfect opportunity. Racism, cultural chauvinism and religious freedom created an American tragedy.

There are many books on Indian-white conflicts. A perennial bestseller, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown (1971), is credited with changing white Americans’ perception of Indians. A recent addition to discussions about the Ghost Dance is God’s Red Son by Louis S. Warren (2017).