Hollywood movies and TV shows often depict lawyers as opinionated blowhards who snivel with fear when the going gets tough. That stereotype doesn’t apply to a guy named Roger.

Roger J. Bushell was born in South Africa in 1910 to English parents who had moved so that his father could take an engineering job with a mining company. Bushell’s family was financially able to send him to an English public school and then to Cambridge University. Bushell was broad-shouldered, just under six feet tall, and enjoyed sports, particularly skiing.

In 1934, Bushell became a barrister. Litigation attorneys need to think quickly under pressure and argue persuasively. They also need to organize swathes of information into a coherent story. These skills would come in handy when Bushell became a prisoner of war (POW).

Bushell joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939 when World War II began. On May 23, 1940, his plane crashed near Boulogne, France. Unfortunately, he landed in territory that had already fallen to the Nazi invasion of France and he became a POW.

As a POW, Bushell became a serial escapee. Once, he reached the Swiss border before being caught. On several occasions, his litigation skills enabled him to talk his way out of severe punishment after recapture. Eventually, he ended up at Stammlager (Stalag) Luft III at Sagan, Germany; now Zagan, Poland.

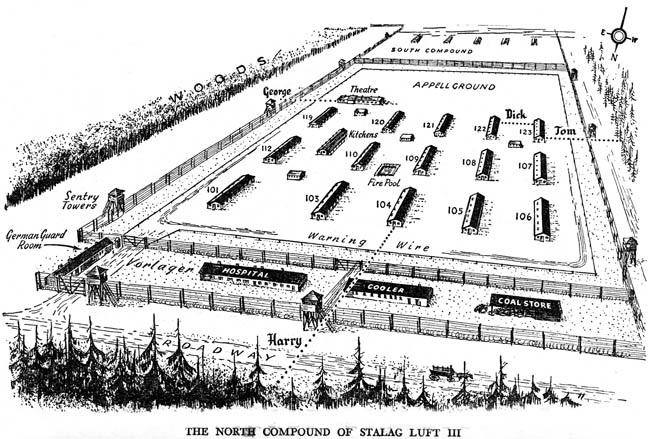

By the time Bushell arrived at the camp, the senior officers had concluded that so many POW’s were trying to escape they were literally tripping over each other, causing all efforts to fail. So the senior POW’s decided to organize all escape attempts in the camp in the hopes this would increase the chances of some of them succeeding.

Bushell was a leader of the escape committee due to his forceful personality and organizational capabilities. He created an “on-boarding” process to assess the skills of each new POW and assign them to an escape team. Teams sewed civilian clothes, made maps and compasses, forged documents, and dug tunnels.

His ability to argue persuasively helped convince the escape committee to support a massive escape. His plan required digging three tunnels simultaneously so that if one tunnel was discovered they could continue with the other two. His plan also envisaged 200 POW’s escaping on the first night with additional escapes on succeeding nights.

During the night of March 23 - 24, 1944, seventy-six men crawled through a tunnel, surfaced beyond the wire, and set off in groups of twos and threes before an alarm sounded. Three eventually made a “home run” to England. The remaining 73 escapees were recaptured and 23 were returned to the Sagan camp.

But 50 were designated for special treatment on the orders of Adolf Hitler who wanted to retaliate against the “terrorfliegers” bombing Berlin and other German cities. Bushell was one of the 50 escapees handed over to the Gestapo to be executed.

Roger Bushell was considered a gifted litigator by his pre-war colleagues. He was also a brave and resourceful fighter during the war.

Today, experienced skiers in St. Moritz can try their luck on the “Bushell Run," a course where he set a pre-war speed record in downhill skiing. Intrepid tourists can visit the camp ruins to see a memorial to the 50 murdered escapees. Another resource is a November 2004 documentary broadcast on the PBS Nova series, which includes an archaeological dig of the tunnel and interviews with survivors.

The most widely read book on Stalag Luft III is The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill (1950). For an in-depth account of the search for the executioners, see The Longest Tunnel by Alan Burgess (1990). Jonathan F. Vance’s A Gallant Company (2000) includes stories of Roger Bushell’s pre-war career as a lawyer and an epilogue with information about the survivors’ post-war lives.

Want to receive this blog straight to your inbox? Sign up for my mailing list.